SPOILER ALERT: This article contains full spoilers for God of War!

To explain the “God of War problem” in its entirety, we have to take a trip down memory lane. In the middle of the last generation of consoles, there seemed to be a cognizant movement to raise the level of quality of narratives in games. Critics started to lambaste titles that did not make honest attempts at telling worthwhile stories with games like Heavy Rain and Mass Effect 2 raising the bar for the industry at large. Motion capture suits began to proliferate around PlayStation’s first party studios and the positive impact it had on their work made games that did not use the technology appear ancient in their approach to cinematics.

By the end of the generation, The Last of Us and BioShock Infinite helped to redefine what games could achieve in the narrative department. It was no longer the case that a game’s story would play second fiddle to the design of its world and the mechanics that were used to interact with it. At the biggest and best studios, stories were now the driving force that dictated the direction and philosophy of a project.

And so have we evolved to God of War – a titanic tale about a titanic man and his very small boy. A title that has almost unanimously been crowned game of the generation in a generation that continues to focus on the importance of storytelling – an aspect of all forms of art that is deeply subjective. And therein lays the problem.

A Flawed Masterpiece

God of War’s reviews are a consequence of objectivity; what can be measured with eyes and ears but not what is felt or what is understood. Objectively, the game has some of the best visuals around. I am sure that the vast majority would also include the combat system as something that can be said to be objectively great or as close to that distinction as possible. What isn’t so objective is the overarching story that takes Kratos and Atreus to the highest point in Midgard and beyond, or the interweaving of the game’s many aspects to create a cohesive piece.

This is where the criticism stops short and doesn’t completely allow us to get into the mind of the critic. Story is one of the only subjective parts of games in this sense, and it is what should be focused on when critiquing games of this sort – titles that claim to place story at the peak of their design hierarchy like those from Naughty Dog and Quantic Dream. Whether or not we, as individuals, agree with what is being said, a focus on the purely subjective aspects of a game will undoubtedly create a more diverse collection of opinions on sites like OpenCritic and Metacritic as opposed to focusing on that which will almost always be agreed upon like graphics and overall gameplay.

This is also where games begin to diverge from other forms of art like that of films – a medium whose critics are forced to speak exclusively in subjective tones. Besides blockbuster visuals in the biggest movies of the summer, every other aspect of a film can only be taken subjectively. Whether one likes a certain cinematic style or how the themes of a story are explored, there is an argument to be had on all sides. The vast majority of gamers, however, will mostly agree on the quality of a certain game’s graphics or its online infrastructure or the feeling of its weapons at the pull of a trigger. So why focus on that which is agreed upon when a story is there to be dissected, especially in narrative heavy games that are marketed as such? This approach would inevitably lead to a wider gamut of opinions making for more interesting reads that don’t begin to all sound the same.

A New Beginning

Now that I’ve gotten that out of the way, let’s analyze the game in question. Does God of War have a great story and one that is good enough to deserve such high praise? Or, is it simply down to a young medium that has yet to find itself and build a comprehensive community of criticism? It is important to note the manner in which God of War has been presented to audiences prior to its launch. It looked to be yet another story-focused epic from the PlayStation first-party; the next coming of a Last of Us-type game, and not just in terms of its quality. Far more importantly, it was all about a sheer focus on storytelling. The developers at Sony Santa Monica have gone on to talk about the next era of the franchise, an evolution of God of War and the Spartan on its cover. I don’t believe God of War merely has a weak story, but that the game is one that doesn’t even seem to be focused on delivering any significant amount of story, nor one that is designed for a story to flourish and take the leading role among the other aspects that make up the adventure.

While The Last of Us and Uncharted consistently deliver a narrative experience, God of War seems content with exploration and combat while sprinkling tidbits of narrative wherever it can find the room. There is no single stretch of the game, besides the flawless quest for the magic chisel when investigating the dead giant, which consistently delivers meaningful narrative content in the way that every second of Naughty Dog’s adventures manage to do. The most obvious example of this is the game’s ten-hour long introduction. Nothing really happens in God of War until you begin to reach its mid-point. The first two or three hours are incredibly slow, although I thoroughly enjoyed this approach to a brave new world that was ours to explore. But all of that goodwill started to erode at hour five and hour six and hour seven as I trudged past yet another puzzle or combat arena or meaningless cutscene without any significant events taking place in the plot.

The Stranger’s arrival sets the story into motion and the ensuing hours introduce a cold world that Atreus is not yet ready to enter. The father-son duo make their way to Alfheim and the player is greeted with some info about the world but nothing that affects this specific story. The “eternal war for the light” that takes place in Alfheim is simply a backdrop for more combat with different enemies, but it doesn’t push the main story forward, at all. While these types of distractions are always welcome, God of War is full of moments when the story just stays static for hours on end and such a level could have been introduced in the sequel when Kratos and Atreus actually get involved in the war. For now, it’s just window-dressing and it feels like the game is padding out its time and trying to throw in as much filler as it can. The last third of the campaign is particularly heinous when it comes to delaying the end of the adventure for no apparent reason. You’ll need this artifact and that treasure and so on and so forth which leads to an ending that couldn’t come soon enough, and one whose impact is marred by the three hours of grinding that leads up to it.

God of War takes a first act story and stretches it to fill an entire game. The opposite can be seen in 343 Industries’ Halo 5: Guardians which bravely, yet foolishly, kills off major characters and changes the entire complexion of its universe in the first five missions. Both games sit on opposite ends of an extreme, and one is not better than the other in this case. Santa Monica could have either made a straight-forward eight-hour adventure wherein this extension of a story that is too small wouldn’t have been so heinous and noticeable, or they simply could have told a larger story that encompassed what will inevitably be included in the next God of War adventure.

Clashing Philosophies

The same can be seen both with the character of Memir and his role as a plot-device as well as the game’s side-quests. Again, in a game where the main story doesn’t move forward at almost any point, it is suicidal to then design the game in a way that forces the player to take on side-quests in order to be powerful enough to continue the main story once again. I say side-quests but, frankly, God of War is split up into equal parts main quest and fetch-quest. Having Memir by our side, quite literally, gives us the opportunity to consume a bit of lore when doing these fetch-quests, but the main story-line once again takes the back seat to item exploration and combat. It’s almost as if he is there to paper over the cracks of a thin story by directing the player’s attention away from the journey to the mountaintop and toward sprinkled tidbits of lore and world-building. Sony Santa Monica just doesn’t seem to be bothered with delivering a constant narrative experience like their fellow first-party studios endeavor to do.

The aforementioned side-quests are for grinding and the main quest gives us the plot for what is really important in the game: Kratos and Atreus. This character introspection is at the heart of God of War and Sony Santa Monica has made it a point to take the tragedy of Kratos in the original games and evolve the Spartan as a character. The idea was to take him from a one-note hero to a complex character that would undergo conflict and change. But what if I were to tell you that Kratos of Midgard is just as one-note as he was in Greece?

In Robert McKee’s storytelling masterclass simply titled “Story,” a work that has been an illuminating resource for the industry’s best writers like Neil Druckmann and Amy Hennig, the legendary scribe so eloquently expresses the fundamentals of characterization stating, “True character is revealed in the choices a human being makes under pressure – the greater the pressure, the deeper the revelation, the truer the choice to the character’s essential nature.”

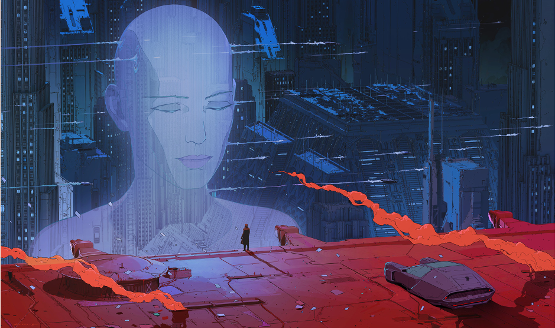

What greater pressure can there be than the imminent death of a child? Over a journey that lasts more than two dozen hours, Kratos of Sparta only endures one moment of the like when he must face the truth of his past to cure his son. In what is unsurprisingly the most revealing, and therefore the most enjoyable, cut-scene in the game, Kratos grapples with the struggle of telling Atreus the truth about his nature. Memir goes on to juxtapose the disconnect between the perception of who one thinks they are versus their conflicting true nature and how Kratos’ refusal to accept his past is beginning to destroy his future – a brilliant examination of the story’s overarching theme and one that is mirrored in works like Blade Runner 2049 with its focus on the interlinking of cells, both inner and outer, to align one’s true nature and become wholly human.

A System of Cells, Interlinked

Unfortunately, that examination comes and goes and we are never presented with another revelation of the like for the rest of the adventure. Everything that occurs at the end has to do with plotting, but not the reveal of true character. This struggle that Kratos and Atreus face lasts about ninety minutes, culminating with Atreus’ momentary fit of rage that doesn’t really end up going anywhere. To compare this to the aforementioned sequel to 1982’s sci-fi classic Blade Runner, the idea of identity and the battle between the inner self and the outer self can be examined in every facet of the film from its character design to the architecture of its world, like the ingenious placement of the Sepulveda Sea Wall jutting up from the Californian horizon and the rising tides of AI anarchy that crash against it.

More importantly, Blade Runner 2049 doesn’t rest on its laurels but instead evolves the theme of its story throughout its nearly three-hour long run time and it consistently has something novel to say about its core theme. God of War comes nowhere near this level of thematic exploration as characters drone on about the same thing over and over again without adding to the theme of the story by drawing from their individual perspectives and backgrounds.

For the rest of the adventure, Kratos is a god-hating, disciplined father with no character arc. He never really goes back to his old self at any point, and it is established very early on that he is past killing gods for revenge – a theme that plays out with the death of Baldur at the end of the game. He is as he was: a one-note character. As for Atreus, the aforementioned moment of madness he is enveloped in doesn’t last for any extended period of time before he goes back to being the same boy he was prior to figuring out his true nature – or half of it, at least. Baldur isn’t on-screen enough to have a complete character arc featuring any significant amount of change and the same can be said about Freya. The two Dwarves and the sons of Odin aren’t really presented as main characters in the same way, so it is easy to forgive their lack of change over the journey.

While what is present in God of War may seem acceptable within the context of the game, its lack of narrative depth, from the angle of its characters, becomes far more apparent when looking to other stories in the same mold. Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us and 343 Industries’ Halo 4 are the two best examples of true character introspection’s that present diametrically contrasting characters at their conclusions than those the player meets at the start of the campaign. Both sets of characters, from the grizzled pair of the Master Chief and Cortana to the more recently established family of two in Joel and Ellie, undergo vast amounts of change and are forced to deal with demanding questions on every step of the journey. From the Master Chief disobeying orders and contemplating the thin line between man and machine to Joel rediscovering what it means to feel, thereby turning from a heartless shell of a man to one who finally decides that some things are worth fighting for.

To make matters worse, like Metal Gear Solid V, God of War isn’t really designed to allow its story to flourish – more evidence that Sony Santa Monica has clearly favored other aspects of the game at the expense of the narrative. With MGSV, we can see that an open-world game in its mold isn’t really suited to tell the kind of story that Hideo Kojima is known for. Other aspects of the game’s design get in the way of allowing the narrative to be the main focus. It really isn’t made, from a design perspective, as a game that centers its design philosophy on its narrative. For example, cut-scenes pop up at odd times and a lot of the story is told through audio log recordings that are meant to be played whilst you’re on a mission which inadvertently means that you may miss parts of the story of the mission you’re playing when Miller or Ocelot chime in with details about your current objective.

God of War is the same; meaningless, from the perspective of the main story, sidequests destroy the pacing of the main quest, which is also hindered by the slow progression of its story because of how much combat and opportunities for upgrade these missions must deliver in a game that is made to be played after the credits roll. The story is seen as epic and meaningful because it is hidden under the deceptive veneer of the game’s production value: a one-shot camera, close-ups depicting an unprecedented level of facial animation, larger than life set-pieces, and seductive teases at the stories end. These are things that are supposed to add to and elevate the core narrative experience which is the dialogue and the character interactions and real stakes and interesting things to do, which all sprout from the expansion of the core theme of the story. They aren’t supposed to be taken as the core of the narrative experience itself, which leads me to my last point to discuss the most telling cut-scene in the game involving Kratos’ old friend.

Going Beyond Good and Evil

To quote Robert McKee again, “A true theme is not a word but a sentence – one clear, coherent sentence that expresses a story’s irreducible meaning.” McKee goes on to explain that the theme of a story is the central idea upon which every strategic decision is pinned upon and an idea that should leave the audience with a plethora of meanings that are yet to be discovered. With God of War, the apparent theme is one of identity and grappling with what has been done in order to find out what to do. The problem is that every single character has the exact same thing to say about the theme of the story. Nobody has any enlightening perspectives on this central theme, so much so that Athena herself utters what has already been heard a dozen times before.

Here is a character that is best placed to reveal a different side of this overarching theme. Who knows more about Kratos’ past and the struggles of identity he is dealing with than this Olympian, or rather the cast of her shadow that Kratos is haunted by? And yet, her potentially cutting words are nothing more than displaced air as she states, “Pretend to be everything you are not…” The player is already aware of this struggle inside Kratos! Instead of using this incredibly pivotal scene to shake the foundation of the Spartan, and therefore the player controlling him, Santa Monica waste the opportunity and use it to deliver a trailer-worthy line that essentially means nothing, especially since Kratos immediately rejects her words after a quick moment of anguish.

There’s a lot of plotting, but not a lot of meaning in God of War. What were the writers trying to accomplish except to present the idea of identity and then let it sit without further exploration? The theme of the story is simply brought up using almost the exact same dialogue as if each character knew the lines of the other. It turns God of War from a potentially meaningful epic to a simple collection of happenings and plot points. We all understand the idea that the story presents, but it doesn’t tell us anything we didn’t know. At that point, what is the point? God of War might as well just have taken the MGSV route, leaving most of its story to be told by Memir as Kratos trudges through the game’s quests in an open-world.

Catalyst for Change

Now, whether or not this breakdown of the game’s overall design and narrative is agreeable to you or not, a focus on these subjective aspects will lead to less of a consensus and more of a discussion as I hope this will prove. Some might argue that game’s with a similar design are just as valid as traditional, linear eight-hour romps that feature little to no side activities, but that can only be done by focusing on aspects like design and narrative and their coming together as opposed to individual aspects of a game that are interpreted without context.

While I sometimes begrudge the incredible range of opinions present for every film on aggregator sites like Rotten Tomatoes, there is something to be said about a group of critics interpreting a work of art with such untroubled individual expression. This is what they really think and there is nothing left on the table. This type of almost overly honest and overly critical culture has its flaws, but it is high time to move on from the traditional ways that games have been approached for the sake of the medium’s growth and its developers, who are always open to a different interpretation of their work if it is honest and unique enough to stand out from the crowd.

The ideas I have presented in this feature, and those that have been discussed in critic circles, won’t just affect games that earn incredibly high scores, but even those like last year’s Mass Effect: Andromeda whose criticism did not come close to exploring all aspects of the game and how they fit together. While I don’t believe that God of War is a “new beginning” for the franchise and one that has evolved from the original trilogy, it may be such a moment for the criticism of games at large as the medium begins to mature and find its own identity like the Ghost of Sparta himself continues to scavenge for.