The Persona series has revitalized the Japanese role-playing genre during an era when it largely seems to have fallen into obscurity in the West. An offshoot of Atlus’ larger Shin Megami Tensei franchise, it’s known for its deeper character development and social simulation elements, both of which have been the primary factor in its monumental success.

With people being at the heart of the series, it should come as no surprise that Persona puts a heavy emphasis on quality writing to flesh these characters out. Because of that, there’s a lot of work that goes into the localization process of bringing the games from their native Japan to the West. It’s not just a matter of translating the text, which is in and of itself a daunting task; there are a number of other factors involved in making the end product appealing and accessible to Westerners.

Thankfully, Atlus U.S.A. — the branch of the company responsible for localization and publishing stateside — has proven themselves more than capable of this task. With that said, their work has too often gone unrecognized; unless you’re constantly paying attention to the industry, there’s a fair chance you don’t know how the process by which these great games got into your hands. With Persona 5 being one of the most highly anticipated games of the year, it’s time to take a closer look back at what went into making the series such a hit in this part of the world.

Cultural Retention

In Revelations: Persona, the Western release of the series’ first game, major alterations met with a less-than-favorable reception. Players weren’t thrilled with the ethnicity of certain characters being outright changed, and some elements were renamed (read: censored) to avoid offending Judeo-Christian sensibilities. That’s why it’s so refreshing to see the most recent Persona titles not only retain, but also explore, Japanese culture in a way that helps make it feel welcoming to players on this side of the globe.

In an interview with Siliconera, Atlus’ Senior Project Manager Yu Namba discussed how the localization team’s approach to tackling native culture changed in the wake of the series’ first entry. Starting with Persona 2: Eternal Punishment, they actively sought to guide non-Japanese players through unfamiliar cultural elements:

I think that was a turning point for the company in terms of localization, where we wanted to keep to the original content as much as possible. Of course, there are so many things that are so different—Japan exclusive, rather—that if you just translate, nobody here on the stateside would understand.

At the same time, especially with the Persona games from Persona 3 onward, the games had so much Japanese content that our goal was to try to maintain that to… I wouldn’t say educate, but maybe introduce Japanese culture to western game players. That’s what we’ve been sticking to up to now.

The setting of Persona 4 probably stands as the series’ most poignant example of this. Where previous titles followed the lives of students in urban locations, the fictional burg Inaba gave players perspective on life in the Japanese countryside. What makes this so compelling is the careful blending of familiar and foreign, a mix that keeps players surrounded with recognizable, universal human ideas while also guiding them into new territory.

Most players, particularly those who have grown up in comparable Western areas, will be likely to understand the frustration and boredom of teenagers stuck in a small town. On the other hand, they might not immediately identify with some of the other details: Yukiko Amagi’s internal struggle about inheriting her traditional family’s inn business, for example, or a heart-rending scene later in the game involving a kotatsu (a low-to-the-ground table that heats people seated underneath). By leaving these elements intact, the impact of small moments is that much more deep (and there’s a minor educational element, too).

Dialogue

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of characters to Persona’s impact as a series. Even with a fairly solid RPG system in place, these titles would never have achieved such monumental popularity without their casts of lovable (and loathable) personalities. Significantly forming these personalities is the way the characters speak, and Atlus’ localizations have certainly not skimped in the dialogue department. Where other games employ a more direct translation that often comes off as a bit wooden, Persona’s chatty characters have had their text deconstructed and rewritten from the ground up for a Western audience.

Social Links, bonds with the other characters which the player can build by making certain choices, trigger cutscenes that delve into each character’s backstory and see them develop over the course of the larger narrative. They’re really the crux of Persona 3 and 4, and a massive amount of work went into making them sound natural for Western gamers. Prior to the latter game’s release, lead editor Nick Maragos spoke to 1UP about the way workflow was broken up; apparently, each editor had specific characters they were assigned. Because this allowed each of them to get familiar with a different set of people, they were often experts at writing the dialogue of the ones they handled; for Social Links involving group meetings, they’d write collaboratively to ensure a consistent voice.

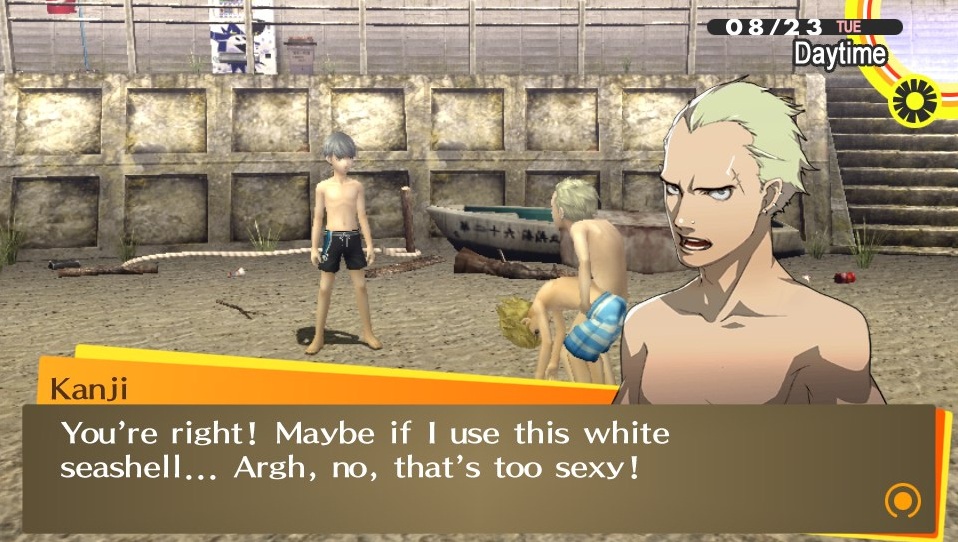

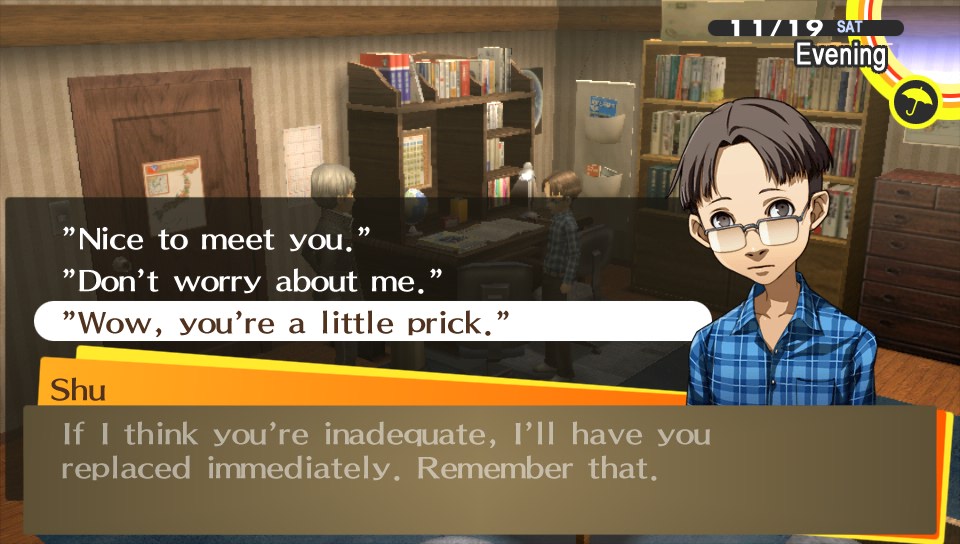

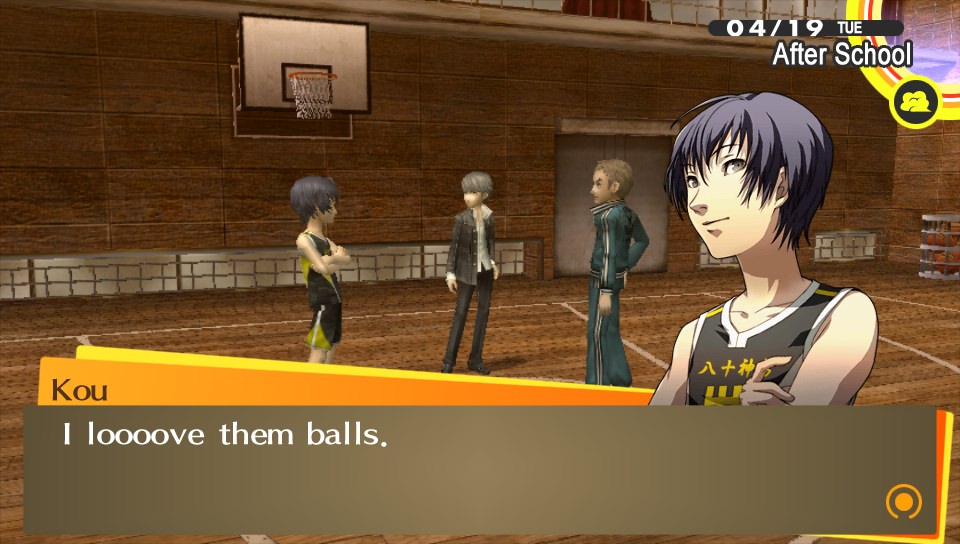

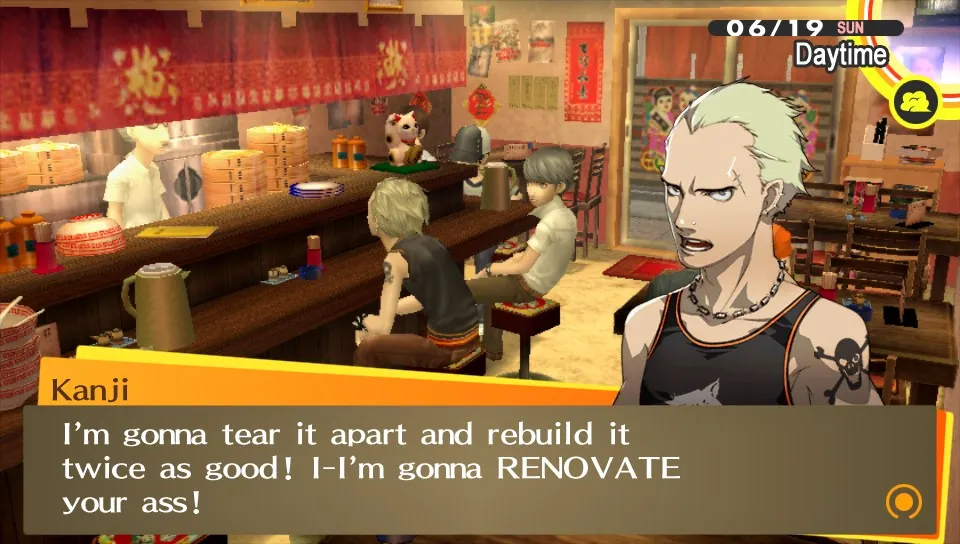

Humor is a touchstone of the localizations, as well, and it’s employed to great effect. Who can forget Kou Ichijo’s bold declaration, “I loooove them balls” in Persona 4 or Shuji Ikutsuki and his obsession with awful puns (including such squirmers as “that was an engine-ous move”) in Persona 3? There are a number of laugh-out-loud moments across the series, particularly in its later installments, that aren’t afraid to really dig into what makes each of the characters so unique and poke fun at them.

In some of the remakes, the writers even throw in tongue-in-cheek references to the localization history of the games themselves. One of the writers for the first Persona’s PSP remake, Scott Strichart, told Gamasutra there were some bits of dialogue referenced or left intact based on their sheer silliness:

I was actually asked to play the original PlayStation version before the project began for reference, and I encountered a line spoken by the Yakuza demon that I screen-capped for the express purpose of retaining it. That line stands out like a sore thumb, so I’m sure you’ll recognize it if you find it. I guess it could be considered homage to how far our company’s localizations have come in the past decade.

Whatever entry you’re playing, here are a number of times you really feel like you’re sitting around, joking around with friends, and the bond you can create with these fictional characters is a testament to the writers’ passions, talents, and senses of humor.

Voice Acting

One of the most common complaints about Western releases of Japanese video games is the exclusion of an option to hear the voice tracks in the original language. Considering the relatively poor quality of some dubs and translations, that’s not exactly a surprise. Fortunately, dealing with such linguistic jankiness is not something fans of Persona have to deal with anymore: Atlus U.S.A. has a consistently phenomenal track record with English voice work. Naturally, requesting subtitled Japanese voiceovers may still be a point of contention, but it’s important to note that dubs of this standard are hard to come by.

Part of Atlus’ dubbing success has to be credited to their recognition that voices are important identifiers for their characters. The localization team struggled to cast an English voice for Golden’s Marie, with Namba emphasizing to Famitsu the significance of finding the right actress; they simply wouldn’t accept casting someone who they couldn’t see embodying their vision of her. The actors they hire seem well-versed in the characters they’re voicing, as well; they’re not just reading the lines, they’re inhabiting the people that speak them. Erin Fitzgerald, who has voiced Chie Satonaka in five games since 2012’s Persona 4 Arena, fell in love with her character and expressed sadness at the possibility of the role ending to Rice Digital:

Chie is a huge part of me. I have not come to terms with the possibility that after [Persona 4: Dancing All Night], I may never get to be her again. I’m guessing I will go through some sort of grieving process but I don’t know when it will kick in. Through the fans she will live on forever.

Atlus has also dealt with a fair bit of challenge with regards to dubbing, particularly when it comes to the Persona 4 cast. As of the release of Dancing All Night, less than half of the party members from the first game are voiced by their original actors. This can be jarring for players, of course, but Atlus — and the actors themselves — haven’t been afraid to address casting changes. For example, before Arena debuted in the West, a representative from Atlus took the time to explain the situation and note the differences; with Dancing on the horizon, Laura Bailey took to Twitter to lament her inability to voice Rise Kujikawa this time around. This recognition, and transparency, is clearly crucial to making the characters feel organic.

The Persona games would be nothing without their writing, and it’s a pleasure to see this crucial factor treated with the same reverence on this side of the globe during the localization process. By incorporating cultural differences rather than erasing them, imbuing the dialogue with enormous personality, and hiring actors that care about the characters they’re voicing, Atlus U.S.A. has helped bring the series to the top of the role-playing heap in the West. Persona 5 can’t come soon enough.

Funny Persona 4 Moments

-

Funny Persona 4 Moments

-

Funny Persona 4 Moments

-

Funny Persona 4 Moments

-

Funny Persona 4 Moments

-

Funny Persona 4 Moments

-

Funny Persona 4 Moments

-

Funny Persona 4 Moments

-

Funny Persona 4 Moments