Xenogears recently arrived on the North American PlayStation Network as a $9.99 download. This excites me, even as someone who has finished the PSX version twice and the Japanese PSN (released in 2008) version via PSP. Originally released in 1998, Xenogears almost didn’t make the trip out of Japan due to heavy religious themes that Squaresoft predicted would upset the Western audience. Thank God (heh) the company went ahead with localization, because despite a few aspects that haven’t aged well, this is an RPG that deserves a try from any fan of the genre.

The legacy of Xenogears today lies mostly in its story, for good reason. While there were great RPG stories before it and even more since its time, Xenogears remains a true legend in the hearts of many longtime RPG lovers. It uses well-developed characters moving through an intriguing plot in ways most other games have only dreamt of. Looking at the whole picture, the way Xenogears‘s plot moves about is truly artful.

First on the screen is an intro video that will probably do more to confuse the player than anything else, as it will be dozens of hours before pieces of its explanation start to emerge in any way at all. It doesn’t take away from the experience, however, as it gradually becomes apparent that this occurrence was particularly noteworthy, the goal of finding out more gets pretty exciting. This is in addition to what’s happening to the characters in real-time, of course. After a brief introduction to the world and its history, players then take control of Fei Fong Wong, a simple villager living in peace. (Very minor spoilers coming, most of which occur in the first bits of the game.) After some character and setting establishment, things start to really move when military opponents piloting huge battle-ready robots crash land in the center of town; their fight actively destroys much of the surrounding area. Fei, though extremely unwilling, ends up having to pilot one of the machines in an attempt to save the town. His efforts are counter-productive, eventually leading to the town being blown off the map — or…world map, as it were. It’s socially best for all survivors if Fei gets out of there. (*End minor spoilers*)

Players will take Fei and his allies through a plot that generally avoids cliché, even thought it’s populated largely by stereotypical JRPG characters. One could make this sound like a movie trailer with lots of “A tale of war’s horror, questionable morality, undying love, betrayal, and murder! Expect the unexpected!” …but such cheese would not do the Xenogears story the serious justice it deserves. Not only does this game’s story manage to stay mostly unpredictable, it’s very well directed. If you ever see people online, making excited comments about the involvement of Tetsuya Takahashi and/or Masato Kato in a video game and are wondering why their names are a big deal, a big part of it is Xenogears. It’s engaging early, and it stays that way throughout its entire 60-85 hours.

The downfall of this lengthy story is that is was actually too long, which brings us to the infamous second disc (referring to the original PSX release; obviously the PSN version does not come with discs). In the second half of the game, the story has a lot of loose ends to tie up but not quite the time to do so with actual gameplay. There are widely mocked instances of characters simply sitting in chairs telling the player about certain events and how they transpired. Now, believe it or not…the strength of the story is actually good enough to balance this out. Oh yeah, this sounds like a red flag, and as someone who complains a lot, it should be right up my ally to lay the hammer on this aspect of the game. But I just can’t; it’s too freaking good.

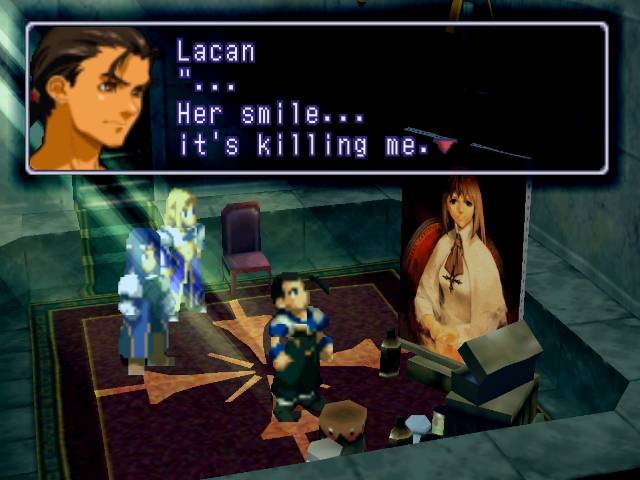

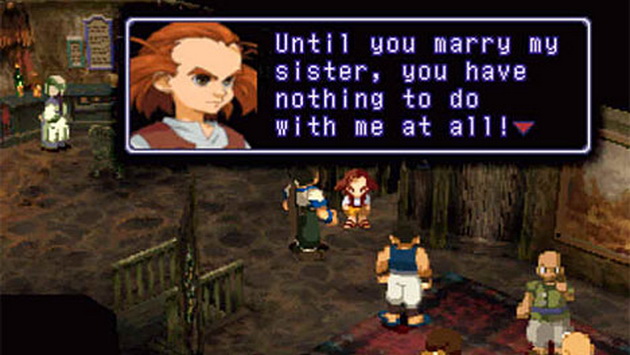

The makeup of the cast itself is where all kinds of RPG clichés show up, but stay with me. OK, so in this game, we’ve got a character with memory loss, a destroyed city or two, a hero who doesn’t want to fight, people with hidden potential/powers, a demi-human, a furball, a smart guy with glasses, a long-haired-and-skinny female love interest, a character with green/blue hair, and enough orphans to form an official Xeno soccer team. Quite the list indeed. Those who’ve never been able to like a JRPG story honestly might not be able to get past all this. Clichés are present in the cast and world of Xenogears, but the story itself is deep, impactful, serious, and well-told. A lot of the themes, especially those delving into Freud’s theories of personality, I didn’t even encounter till my last year of college. Imagine my surprise when I was thinking “Wait, so this is what those guys were talking about in Xenogears?” Mind blown. That’s pretty impressive for a video game, you gotta admit.

Some English dialogue bits suffer in Xenogears. For whatever reason(s) — maybe a smaller budget, perhaps due to RPGs still not being a megahuge mainstream presence back in 1997-98, or some combination of the two — the script has a number of encounters with awkward sentences, unnatural wording, and jarring changes of tone that were perhaps accidental or unrealized by the original translators. There’s nothing on par with “All your base are belong to us,” thankfully, but the game can sometimes be vague or unclear, which doesn’t help a game whose story is already a little hard to take in. Most of these problems don’t exist in the Japanese version, but the complicated nature of the plot and subject matter will be discouraging, even to many players who’ve imported other games. Thankfully, even with the occasional funny-sounding script, the meaning of a given sentence remains clear, especially in the cutscenes and most important moments of intra-party discussion.

The music of Xenogears is a fine example of Yasunori Mitsuda’s auditory mastery, and it assists the storytelling at every turn. Its soundtrack is hands-down one of the best in gaming, with compositions that fit their scenes perfectly, capturing the emotions of the characters and world around them. Even the town BGMs are worth high praise. It’s one of few game soundtracks that, for me, remains powerful and enjoyable outside of the game — even 12 and a half years later.

Gameplay in Xenogears rolls along in usual JRPG fashion, with expected importance being placed on the navigation of dungeons, defeat of random enemies and bosses, romping around various towns, and trekking across a big ol’ map of the world. The dungeons are quite fun and feature great layouts, and occasionally, some nicely done puzzles. The only complaints are that sometimes random battles come at an annoyingly high rate, and a few segments of required jumping tend to be frustrating. One aspect of Xenogears that impressed me the first time I played it and still does today is its towns. Cities in Xenogears are seriously fun and rewarding to explore, and players will find themselves wrapped up in their own self-created goals of going everywhere, jumping over/off of ridiculous things, talking to everyone, and doing all the neat little asides. Bledavik in particular is great fun the first time around, but others are also fascinating specimens of great RPG design. Old time RPG fans who find today’s lack of overworld maps disappointing will find something to love with Xenogears, as it reminds players of old times, when such was a staple of the genre.

“Deathblows” are central to combat in Xenogears. There are two battle systems used throughout the game — one for on-foot characters and one for the giant robots called “Gears,” after which the game is named. These two serve as different spins on a similar root system. On foot, a character begins with a certain amount of attack points to use in his/her turn. Triangle is a light attack that costs one point, square is medium and costs two, while X is the heaviest blow and costs three points. Some certain combinations will form a more powerful attack than its components; this is the Deathblow. For example, if Fei is at the point where he’s only got five attack points and uses X (three points), the player can stop the attack right there, or toss in a square attack for good measure — or two triangle attacks for that matter. Those, however, are not as powerful as hitting those buttons in the reverse order, as square-X is one of Fei’s Deathblows. Entering this special combination causes Fei to jump up and do something reminiscent of a Liu Kang bicycle kick, dealing more damage than the smaller attacks that form it. The player can use whatever combination of these to fill use up all the points, or halt to save up AP. This practice does not allow the use of more AP in the next turn, but can make future actions somewhat more powerful, so there’s some strategy in deciding when to attack in what way.

Gear battles operate similarly, though a little more restricted, as the number of attack points and amount of potential combos is much lower. There’s also the variation of all gear actions needing fuel. An X attack, for example, might need 30 fuel while a triangle attack only needs 10. A Deathblow in a gear could need 50 or so. The gear battles take longer than the character fights to really get interesting, but eventually they are a fun form of RPG combat, and if nothing else, the systems taking timeouts from each other seems to enhance both.

Where players might be a little puzzled is the game’s lack of explanation of any of this. In the game’s menu, one’s progress toward the learning of new deathblows can be seen on percentage meters, but there’s no indication as to what exactly moves them forward. It’s not simple fighting, it’s not use of other deathblows, it’s not use of funky combinations, it’s an extremely complex algorithm whose explanation isn’t even attempted. Furthermore, a certain deathblow might be listed as 100%, but the character can’t perform it yet. As a multi-time vet, I’ve learned to not worry much about what the status screen says and just roll with it, but this will be confusing to new players. Just the same, the combat is fun enough, and that’s what matters more.

There are other interface and control-related issues that sadly show the game’s age. There is no way to speed up the painfully slow text, and in a game with as much non-voiced talking as this one, that can be a little frustrating at times. Some shop menus are often quite inefficient, not allowing the player to do very much investigation of items/equipment before buying and often not letting one buy and sell in a single store entry. One example is when stores sell multiple kinds of products, like gear stuff and human stuff. Entering the store’s menu and selecting to buy “Gear Parts” brings one to the appropriate place, but then the player has to exit the menu entirely and talk to the shop owner again, hear his slowly typed speech on the war in Aveh again, and enter the menu anew in order to buy some standard items. Little stuff like that, all over Xenogears‘s menus and controls, are a sad reminder of its age and budget. But don’t let the length of my paragraph here seem like a big complaint. It should be said again that while Xenogears has a basketful of small hindrances like these, they’re squashed under the power of the game’s strengths.

Saying that Xenogears is graphically impressive will probably raise some eyebrows of newcomers and younger gamers who’ve been growing up in the flatscreen/HD era. The first thing players might zero-in on is the pixelated character sprites and refute my praise of its visuals. But consider this: Xenogears had a fully rotatable camera — indoors, outdoors, and on the world map — when extremely few RPGs did. We’re talking about a game that came out in 1998. One might point to Parasite Eve and Final Fantasy VII as games that came out in the same era but looked more polished, but those games have pre-rendered, unchanging backgrounds. Only on the world map did Final Fantasy VII allow manual camera rotation, while Xenogears allows it virtually everywhere; this takes a lot of disc space and a lot more work on the part of developers, and the payoff is a more immersive experience. Its backgrounds, towns, battleships, and gears all look quite good, and its pixelated sprites actually look better than before, on the PSP.

On that topic, a fun historical note is that Xenogears was also the first Squaresoft game to use voice fully voice-acted cutscenes and the first to use Japanese anime sequences. The game has a little over 20 minutes of these in all. They’re very well done, but often a little short, and it’s sort of a bummer to only get them so sporadically over the long playtime. Like some other things, this was probably due to budget issues of the time. Still, what’s there is great.

Xenogears is one of the best RPGs of the PSX era, one of the best RPGs of the 1990’s, and to a lot of gamers, one of the best RPGs of all time. Being so readily available at only 10 bucks, JRPG fans who missed it in its heyday should pick this up without hesitation. Much like classic films such as Citizen Kane or Casablanca, it will perhaps not be as stunning to the youth of today as it was when it was first released, but observing this important piece of gaming history is definitely worthwhile. After all this time, its story and music still live on as legendary, its battles and dungeons are still good fun, and the game as a whole should not be missed.

PlayStation LifeStyle’s Final Score

+Gameplay still interesting and fun after all this time. -Several archaic control/interface issues have definitely not aged well. |

|

–